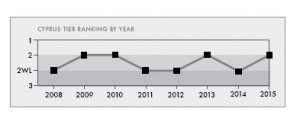

CYPRUS: Tier 2

Cyprus is a source and destination country for men, women, and children subjected to forced labor and sex trafficking. Victims identified in Cyprus in 2014 were primarily from Eastern Europe and South Asia. In previous years, victims from Africa, Dominican Republic, and Philippines were also identified. Women, primarily from Eastern Europe, Vietnam, India, and sub-Saharan Africa, are subjected to sex trafficking. Sex trafficking occurs in private apartments and hotels, on the street, and within commercial sex trade outlets in Cyprus including bars, pubs, coffee shops, and cabarets. Foreign migrant workers—primarily Indian and Romanian nationals—are subjected to forced labor in agriculture. Migrant workers subjected to labor trafficking are recruited by employment agencies and enter the country on short-term work permits. After the permits expire, they are often subjected to debt bondage, threats, and withholding of pay and documents. Asylum seekers from Southeast Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe are subjected to forced labor in agriculture and domestic work. Unaccompanied children, children of migrants, and asylum seekers are especially vulnerable to sex trafficking and forced labor. The Government of Cyprus does not fully comply with the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking; however, it is making significant efforts to do so. During the reporting period, the government convicted three traffickers and punished them with the most stringent sentences ever issued for a trafficking crime in Cyprus since it was criminalized in 2000. Authorities launched more investigations than in 2013 and achieved the first two convictions for child sex trafficking. The government nearly doubled the number of victims identified and, despite cuts in benefits in other social welfare funding, it maintained financial resources allocated to shelter victims. Reports persisted, however, of substantial delays in the issuance of monthly public allowance checks to some victims. Male victims identified in early 2015 did not receive benefits and relied exclusively on NGOs for care. Experts reported insensitive and sometimes punitive treatment of victims by the Social Welfare Service, with some victims sent to unsuitable and exploitative jobs.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CYPRUS:

Improve efforts to vigorously prosecute trafficking offenses and convict and punish traffickers, including officials who are complicit in trafficking; provide increased services for male victims, including shelter; provide financial allowances for victims in a timely manner; conduct a review of practices employed by the Social Welfare Service in securing employment and accommodation for victims; train Social Welfare Service staff in best practices of victim care; continue to raise awareness of trafficking and victim identification among police and migration authorities and provide training on victim identification, particularly for forced labor; further train judges and prosecutors to ensure robust application of the new anti-trafficking law; continue increasing the use of expert witness testimony in prosecutions of trafficking offenses and adequately protect victims during court proceedings; formalize the national referral mechanism to provide a practical guide that clearly outlines the roles and responsibilities of front-line responders, respective ministries, and NGOs; launch a study of visa regimes for performing artists, students, barmaids, domestic and agricultural workers, and other categories to identify potential misuse by traffickers; and increase screening for trafficking among visa holders in vulnerable sectors.

PROSECUTION

The government increased law enforcement efforts. Cyprus prohibits all forms of trafficking through Law 60(I) of 2014. Prescribed penalties are up to 20 years’ imprisonment, which are 139 CYPRUS sufficiently stringent and commensurate with those prescribed for other serious crimes. The government investigated 24 new cases involving 35 suspected traffickers during the reporting period, an increase compared with 15 cases involving 33 suspects in 2013. The government initiated prosecutions against 15 defendants, a decrease compared with 22 in 2013. Nine traffickers were convicted under Law 87(I)/2007, Law 60(I)/2014 and other laws, compared with two in 2013. Sentences were significantly more stringent than the previous reporting period. Eight of the convicted traffickers received time in prison ranging from three months to 12 years; one convicted trafficker did not receive any time in prison. One case led to the first conviction for trafficking of a child for sexual exploitation; the two perpetrators, both Cypriots, were sentenced to 12 and 10 years in prison. The government continued to convict traffickers under non-trafficking statutes, leading to lenient sentences for convicted traffickers. The anti-trafficking police unit provided oversight throughout the course of an investigation; however, the court system’s mistreatment of victim witnesses and lengthy trial procedures resulted in a limited number of convictions. The government did not effectively track trafficking cases as they moved through the judicial system. The government established a mechanism to review labor complaints, and officials forwarded potential forced labor cases to the police and the social welfare department; however, NGOs reported officials rarely treated labor complaints as potential trafficking cases. The government installed new software for the anti-trafficking police unit to enhance its capacity to record, process, and analyze trafficking-related data. In 2014, the government funded antitrafficking training for 86 law enforcement officers, as well as a joint training for police and prosecutors to enhance cooperation. NGOs reported allegations of official complicity involving at least two senior officials and one former official who solicited services from a sex trafficking victim. The case was acquitted after the court ruled the victim’s testimony was unreliable. A police immigration official acquitted in 2012 for alleged involvement in a sex trafficking case won his suit against the government contesting his dismissal. He was rehired and placed in charge of the immigration service at Larnaca Airport; NGOs have strongly protested his appointment to such a sensitive position.

PROTECTION

The government increased efforts to protect victims. The government maintained financial resources allocated for victims despite cuts in other social welfare funding. The government identified 46 victims of trafficking in 2014, an increase from 25 in 2013. Of the 46 victims identified, 22 were labor trafficking victims, of which 15 were men and 7 were women. The government identified 19 victims of sex trafficking, including 16 women and three children. Five additional women were victims of both labor and sex trafficking. Most victims of forced labor were referred to the police by NGOs. The majority of sex trafficking victims were identified during police operations. The government referred all identified victims to the social welfare office for assistance. Twenty female victims of sex trafficking were accommodated at the government-operated shelter in Nicosia. These victims were permitted to stay for one month or longer, as appropriate, in the shelter for a reflection period, a time in which victims could recover before deciding whether to cooperate with law enforcement. In previous years, authorities accommodated male sex trafficking victims in hotels paid for by the government; male and female victims of labor trafficking stayed in apartments and received rent subsidies from the government. Multiple sources reported substantial delays in issuance of monthly allowance checks to some victims, which left victims unable to cover basic needs; some male victims were homeless as a result. Male victims of labor trafficking identified in 2015 did not receive benefits and relied exclusively on NGOs for care. Experts reported Social Welfare Service (SWS) staff in Nicosia exhibited insensitive and sometimes punitive treatment of victims. Victims were sent to unsuitable and exploitative jobs where they were expected to work for more hours than legally permitted and received salaries below the minimum wage. If victims declined a job offer, SWS declared victims voluntarily unemployed and discontinued their benefits. The government spent 184,000 euro ($151,000) to operate the trafficking shelter, compared with 199,136 euro ($164,000) in 2013. The government provided 118,066 euro ($97,000) in public assistance to victims who chose to stay in private apartments and were entitled to a rent subsidy and monthly allowance, compared with 262,000 euro ($319,000) in 2013. Victims had the right to work and were provided a variety of assistance and protection from deportation. They also had eligibility for state vocational and other training programs and the ability to change sectors of employment. A lack of directives on coordination between ministries reportedly led to gaps and delays in services and support provided. The law stipulates victims be repatriated at the completion of legal proceedings, and police conducted a risk assessment for each victim prior to repatriation. Two victims whose safety was assessed to be at risk were issued residence permits on humanitarian grounds and remained in Cyprus. Authorities extended the work permit of a third victim. Forty-six victims assisted law enforcement in the prosecution of suspected traffickers. There were no reports of victims inappropriately penalized for unlawful acts committed as a direct result of being subjected to human trafficking.

PREVENTION

The government maintained prevention efforts. The Multidisciplinary Coordinating Group to combat trafficking coordinated the implementation of the 2013-2015 National Anti-Trafficking Action Plan. NGOs reported cooperation with the coordinating group greatly improved during the reporting period. In 2014, the government investigated seven cases of potential labor exploitation of migrant workers for illegally operating an employment agency and revoked the licenses of two private employment agencies for not complying with regulations. The government reported five ongoing investigations of recruiters and brokers for exploitation of migrant workers. The government continued to print and distribute booklets in seven languages aimed at potential victims on the assistance available to them. The government did not report efforts to reduce the demand for forced labor or commercial sex acts. The Ministry of the Interior provided training to labor inspectors, labor relations officers, social welfare officers, and officials in the Ministry of Health on labor trafficking and the provisions of the new 2014 trafficking law. It also included a segment on trafficking in the curriculum for students aged 15-18 years. The government provided anti-trafficking training or guidance for its diplomatic personnel.

AREA ADMINISTERED BY TURKISH CYPRIOTS

The northern area of Cyprus is administered by Turkish Cypriots. In 1983, the Turkish Cypriots proclaimed the area the independent “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” (“TRNC”). The United States does not recognize the “TRNC,” nor does any other country except Turkey. The area administered by Turkish Cypriots 140CZECH REPUBLIC continues to be a zone of impunity for human trafficking. The area is increasingly a destination for women from Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and Africa who are subjected to forced prostitution in night clubs licensed and regulated by Turkish Cypriots. Nightclub owners pay significant taxes to the Turkish Cypriot administration, between eight and 12 million dollars annually according to media reports; additionally, owners pay approximately $2,000 per woman in fees to the authorities, which may present a conflict of interest and a deterrent to increased political will to combat trafficking. An NGO reported girls as young as 11 were victims of sex trafficking inside the walled city of Nicosia. Men and women are subjected to forced labor in industrial, construction, agriculture, domestic work, restaurant, and retail sectors. Victims of labor trafficking are controlled through debt bondage, threats of deportation, restriction of movement, and inhumane living and working conditions. Labor trafficking victims originate from China, Pakistan, Philippines, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Vietnam. Women who are issued permits for domestic work are vulnerable to forced labor. An NGO reported a number of women enter the “TRNC” from Turkey on three-month tourist or student visas and engage in prostitution in apartments in north Nicosia, Kyrenia, and Famagusta; some may be trafficking victims. Migrants, refugees, and their children are also at risk for sexual exploitation. If the “TRNC” were assigned a formal ranking in this report, it would be Tier 3. Turkish Cypriot authorities do not fully comply with the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking and are not making significant efforts to do so. The area administered by the Turkish Cypriots lacked an anti-trafficking “law.” Turkish Cypriots did not keep statistics on law enforcement efforts against trafficking offenders. The area administered by Turkish Cypriots lacked shelters for victims, and social, economic, and psychological services for victims. During the reporting period, police conducted several raids of nightclubs resulting in the arrest of possible victims of trafficking. Local observers reported authorities were complicit in facilitating trafficking and police continued to retain passports upon arrival of women working in night clubs. An anti-trafficking amendment to the “criminal code” was tabled during the previous reporting period; however, no progress was made on enacting it during 2014. The “attorney general’s office” sentenced one “official” to nine months imprisonment for involvement in a trafficking-related case in 2013. Turkish Cypriots did not enforce the “law” stipulating nightclubs may only provide entertainment such as dance performances. Authorities did not acknowledge the existence of forced labor. There was no “law” that punished traffickers who confiscate workers’ passports or documents, change contracts, or withhold wages to subject workers to servitude. Turkish Cypriots did not provide any specialized training on how to investigate or prosecute human trafficking cases. Turkish Cypriot authorities did not allocate funding to antitrafficking efforts, police were not trained to identify victims, and authorities provided no protection to victims. Police confiscated victims’ passports, reportedly to protect them from abuse by nightclub owners who confiscated passports. Foreign victims who voiced discontent about the treatment they received were routinely deported. NGOs reported women preferred to keep their passports but were convinced to give them to police to avoid deportation. Victims of trafficking serving as material witnesses against a former employer were not entitled to find new employment and resided in temporary accommodation arranged by the police; experts reported women were accommodated at night clubs. The Turkish Cypriot authorities did not encourage victims to assist in prosecutions against traffickers, and all foreign victims were deported. If a victim requested to return to their home country during an interview with authorities, they were required to return to and lodge at a hotel until air tickets were purchased. Witnesses are not allowed to leave the “TRNC” pending trial and are deported at the conclusion of “legal” proceedings. In 2014, authorities issued 1,168 hostess and barmaid six-month work permits for individuals working in approximately 40 nightclubs and two pubs operated in the north. An NGO reported authorities did not consistently document the arrival of women intending to work in nightclubs. The majority of permit holders came from Moldova, Morocco, and Ukraine, while others came from Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Paraguay, Russia, and Uzbekistan. Women were not permitted to change location once under contract with a nightclub, and Turkish Cypriots deported 395 women who curtailed their contracts without screening for trafficking. While prostitution is illegal, female nightclub employees were required to submit to biweekly health checks for sexually transmitted infection screening, suggesting tacit approval of the prostitution industry. Victims reported bodyguards at the night clubs accompanied them to health and police checks, ensuring they did not share details of their victimization with law enforcement or doctors. Turkish Cypriots made no efforts to reduce demand for commercial sex acts or forced labor. The “law” that governed nightclubs prohibits foreign women from living at their place of employment; however, most women lived in group dormitories adjacent to the nightclubs or in other accommodations arranged by the establishment owner. The nightclubs operated as “legal” businesses that provided revenue to the “government.” The “Nightclub Commission,” which composed police and “government officials” who regulate nightclubs, prepared brochures on employee rights and distributed them to all foreign women upon entry. They also established a hotline for trafficking victims; however, it is inadequately staffed by one operator.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR TURKISH CYPRIOT AUTHORITIES:

Enact “legislation” prohibiting all forms of human trafficking; screen for human trafficking victims within nightclubs and pubs; increase transparency in the regulation of nightclubs and promote awareness among clients and the public about force, fraud, and coercion used to compel prostitution; provide funding to NGO shelters and care services for the protection of victims; investigate, prosecute, and convict officials complicit in trafficking; provide alternatives to deportation for victims of trafficking; and acknowledge and take steps to address conditions of forced labor